For example, in chapter VII on Gordian, he writes: “It has always been my practice,” wrote Gibbon, “to cast a long paragraph in a single mould, to try it by my ear, to deposit it in my memory but to suspend the action of the pen till I had given the last polish to my work.”ĭecline and Fall is a cathedral of words and opinions: sonorous, awe-inspiring and shadowy, with odd and unexpected corners of wit and irony, concealed in well-judged footnotes. Next to his learning, there’s his style, whose later devotees include both Winston Churchill, ( No 43 in this series), and Evelyn Waugh. Gibbon alludes to passages in Strabo, Sallust, Seneca, Macrobius and Longinus, among many others. It was commonplace in Augustan England of the 18th century to refer to Virgil, Ovid, or Plutarch. Gibbon may have been an amateur historian (his life was otherwise devoted to nurturing his family’s considerable wealth, and to serving in the militia), but his erudition is staggering. In so doing, Gibbon traces the intimate and profound connection of the ancient world to his own, more modern time, linking more or less explicitly the age of the Enlightenment to the age of Rome. The six volumes (published between 17) fall into three parts: from the age of Trajan to “the subversion of the western empire” in 395 AD from the reign of Justinian in the east to the second, Germanic empire, under Charlemagne, in the west and from the revival of this western empire to the fall of Constantinople in 1453. An object of awe, Gibbon’s history unfolds its narrative from the height of the Roman empire to the fall of Byzantium.

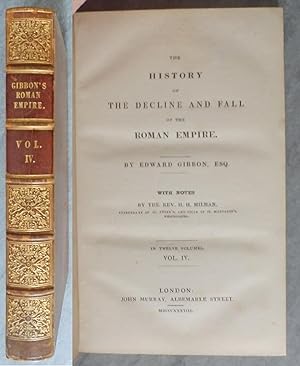

Edward Gibbon almost certainly contrived this fanciful recollection, but the scholarship that went into his Decline and Fall still stands, like a timeless Roman ruin: majestic, elegant and even sublime.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)